The Resilient Knee Project

Why Strength Isn’t Enough, and What Will Really Fix Your Knee Pain

When you’re struggling with knee pain, the first instinct is often to get stronger.

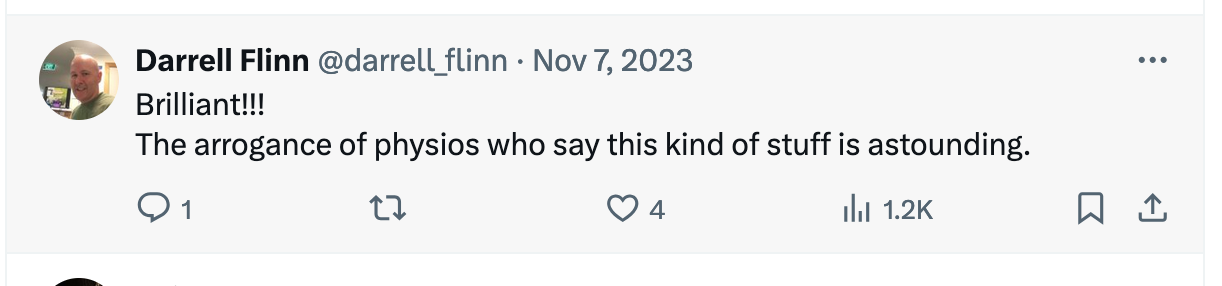

You’re told by well-meaning therapists, trainers, and experts, “If you’re in pain, just build up your muscles.”

And on the surface, that makes sense, right?

After all, strength equals stability, and stability should equal less pain.

But here’s the harsh truth: Strength alone won’t fix your pain.

In fact, if all you’re doing is trying to get stronger without addressing the bigger picture, you could be making things worse.

The Problem: Chasing Strength Without Capacity

Let’s use a simple metaphor: Imagine you’re really thirsty.

You grab a small cup and start filling it with water, but before long, it overflows—water spills everywhere.

That overflow? That’s your soreness, your pain.

Naturally, you think, “I need a stronger cup!”

So, you reinforce the cup, making it sturdier and thicker.

But here’s the catch—now, the cup is more rigid.

And what do we know about rigid things?

They’re more likely to crack or break under pressure.

This is exactly what happens when you chase strength without increasing your capacity.

Sure, you’re getting stronger, but without expanding how much your body can handle, you’re setting yourself up for failure.

When you overload a rigid, small cup (i.e., only focus on strength without increasing function), you’ll keep overflowing.

You might even break the cup.

What you really need is a bigger cup—more capacity, not just more strength.

The Truth About Strength: It’s Not the Only Answer

The “strength fixes pain” myth is powerful, but misleading.

Strength alone won’t solve the issue because it doesn’t address the root of the problem—your body’s capacity to handle load, recover, and adapt.

Without increasing your overall capacity—how well your muscles, tendons, bones, and joints can deal with stress and recover from it—focusing on strength alone makes you more fragile.

It’s like having a stronger but still small and rigid cup. Eventually, it will crack under the pressure of all the load you’re placing on it.

And here’s where it gets worse: The simplistic advice of “just get stronger” carries a subtle but harmful message that you’re “weak,” which can make you feel fragile.

It reinforces the idea that your body isn’t capable, and this fear creates a vicious cycle—making you feel more out of control over your symptoms.

The Solution: Capacity and Functional Resilience

What you truly need is functional capacity.

Instead of focusing on just getting stronger, focus on expanding your body’s ability to handle load without breaking down.

Think of this as building a bigger cup—one that can hold more without spilling over.

Capacity is your body’s ability to not only manage the load but also clear out the “waste” that builds up—like lactate, a byproduct of intense activity.

When your body can’t clear this waste efficiently, it contributes to soreness and pain.

Here’s the good news: Your body is designed to use lactate as fuel when your systems are functioning well.

And that’s where mitochondrial health comes in.

The more mitochondria you have, and the healthier they are, the better your body can clear waste and generate energy.

That’s capacity in action—building not just strength but the ability to handle and recover from stress over the long term.

The Resilient Knee Project: A Different, Innovative Approach to Knee Health

This is exactly what The Resilient Knee Project is all about.

It’s not just about building strength; it’s about creating resilience through functional capacity.

And running, believe it or not, is the perfect way to do this.

We need to respect the high load and force that running provides.

If channeled correctly, those forces can create resilience in your bones, muscles, tendons, and joints.

This is the real strength we’re after: genuine, long-term capacity.

Running builds capacity, but here’s the catch—it takes time.

Months, even years, to fully develop.

You won’t see immediate results.

This isn’t a quick-fix solution, but it’s one of the best long-term investments you can make in your body’s health.

What you’re developing is a powerful physical asset that will serve you for the rest of your life.

Once you build this capacity, you’ll have the knowledge and skills to manage your knee pain independently.

You’ll become the expert on your own body, and you’ll no longer need to rely on therapists or experts to “fix you” with simplistic solutions.

No more embarrassing narratives about being weak.

No more relying on medication, surgery, or avoiding movement out of fear.

Why the Desire for Strength is So Intuitive

Now, let’s address something important: the desire to get stronger is incredibly intuitive.

It makes sense—if you’re in pain or feeling fragile, getting stronger seems like the most logical response.

Most healthcare professionals will validate this desire, telling you strength is the solution.

But remember, strength alone isn’t enough.

Think of it like David vs. Goliath. David didn’t win by matching Goliath’s strength—he won with strategy.

And that’s exactly what you need: a strategy, not just a single-focus tactic like strength.

Your desire to be stronger is good, but we need to unpack it and turn that motivation into something more useful.

The real solution lies in building capacity.

This means not just lifting more weight but knowing when to push, when to back off, and how to recover. You’ll know exactly what to do when flare-ups occur (because let’s be real—they will still happen, just less often and less severe).

The Bottom Line: Invest in Capacity, Not Just Strength

If you’ve been chasing strength to fix your knee pain, it’s time to take a step back and look at the bigger picture.

Strength is important, but it’s only part of the solution.

What you need is to build capacity—giving your body the tools to handle life’s demands without breaking down.

Next time you feel the urge to just “get stronger,” remember: It’s not about building a stronger cup—it’s about building a bigger, more resilient one.

And if that sounds like a good plan to you, know this: It’s going to take investment.

But think of it as the best investment you’ll ever make.

Once you restore function and capacity, no one can take that away from you.

Imagine all the years ahead filled with physical activity, running races, hiking mountains, enjoying great times with friends and family—all without the fear of your knee letting you down, without being stuck in the endless cycle of rehab purgatory.

The Resilient Knee Project isn’t just about fixing pain.

It’s about empowering you to take control of your body, build long-term resilience, and live without limits.

Dan O'Grady is a results driven qualified Physiotherapist and member of the Australian Physiotherapy Association. Dan has a special interest in treating knee pain. He has been working in private practice for 20 years. He is passionate about helping people to move better, feel better and get back to doing what they love.