Moseley’s Red/Blue Light Study: Why It’s Time to Move On

Let’s talk about Moseley’s infamous red/blue light study—a research piece from nearly 20 years ago that somehow still gets rolled out as a cornerstone of pain science education.

It’s a clever experiment, sure, but it’s wildly overused to justify his unwavering commitment to the neuromatrix model.

Here’s the thing - it’s an extremely superficial look at pain that doesn’t hold up when you dig deeper.

Worse, its oversimplified conclusions have caused real-world harm to patients and clinicians alike.

I think it’s to time we moved on.

What Does the Study Actually Show?

In the study, a noxious cold probe was paired with either a red light (associated with danger, tissue damage) or a blue light (associated with cold, less dangerous).

Participants rated the pain unpleasantness as higher with the red light, but pain intensity—how physically strong the pain felt—didn’t change.

This means that context (the visual cue) affected the emotional evaluation of pain (unpleasantness) but not the raw sensory experience (intensity).

This is an interesting finding—but very narrow.

It’s about exteroception (external cues like vision) influencing pain perception.

That’s fine for a lab-controlled experiment on acute pain, but it tells us nothing about interoception, chronic pain, or the real-world complexity of pain.

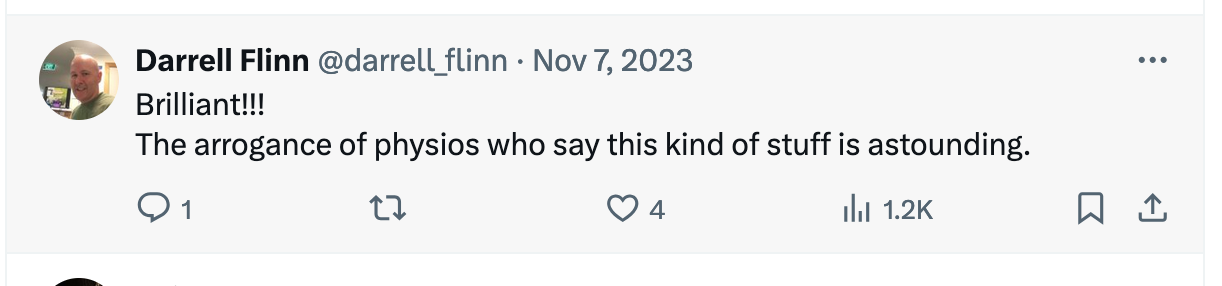

In a recent 2023 podcast, Moseley doubled down on his study with this quote:

“There were some people for whom, with the blue light they reported no pain and with the red light they reported pain eight out of ten. And that’s a very severe pain. There are other people who reported the same level of pain in each situation. And in scientific terms we describe those people as idiots (laugh) because their brains are not picking up on these cues that everyone else is picking up on.”

This is deeply problematic for several reasons:

Dismissive attitude: Referring to participants as "idiots" because they didn’t conform to the expected pattern is disrespectful and ignores the complexity of individual pain responses and the fact that they can trust their bodies experience without being contaminated with external distractions (a rare and amazing skill to be honest)

Moseley uses phrases like "pain eight out of ten" without distinguishing whether he means intensity (strength) or unpleasantness (emotional impact). However, based on the study results, the only dimension that showed such variability in response to the cues was pain unpleasantness, not intensity. This lack of clarity can be misleading

Pain intensity and pain unpleasantness are distinct dimensions, and conflating them obscures the actual findings of the study. It risks overstating the impact of visual cues, as they DIDN’T alter the sensory intensity of the pain but only its EMOTIONAL interpretation.

Failure to update his model: Instead of recognizing that his study barely scratches the surface of pain complexity, Moseley doubles down on his original findings, refusing to appreciate their limited scope.

Ignores interoception and chronic pain: His study is about acute nociceptive pain modulated by visual cues. Chronic pain, which involves interoceptive processes (e.g., inflammation, fatigue, homeostatic dysregulation), isn’t even in the same ballpark.

Moseley’s study isn’t a bad experiment—it’s just wildly overgeneralized. Here’s why:

It only applies to exteroceptive pain: The study is about surface-level pain influenced by external cues (red/blue light). It says nothing about deeper, interoceptive pain (e.g., from muscles or organs), which involves different brain regions like the insular cortex.

It separates pain intensity from unpleasantness: The findings show that context changes unpleasantness (salience), NOT intensity.

But in real-world chronic pain, those dimensions are deeply intertwined and modulated by systemic factors like inflammation and central sensitization.

It ignores chronic pain altogether: Chronic pain is a much messier phenomenon involving altered interoception, disrupted homeostasis, and central sensitization. This study doesn’t even begin to address that complexity.

Unintended Harmful Consequences

By clinging to this superficial study, Moseley’s work has contributed to serious downstream problems:

Gaslighting patients: Patients with chronic pain are often told their pain is just a "brain output," implying it’s all in their head. This dismisses the real interoceptive and structural factors driving their pain, leaving them feeling invalidated and alienated.

Oversimplified treatments: The idea that context alone can “rewire” pain has spawned treatments that focus on changing the brain’s interpretation of pain while ignoring physical contributors like mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, and recovery deficits.

Therapist confusion: Clinicians trying to reconcile this brain-centric model with their patients’ real-world experiences often find it doesn’t work. Chronic pain doesn’t behave like the tidy pain in Moseley’s lab study, and therapists are left frustrated and unsure how to help.

Bud Craig’s Interoceptive Model: A Better Framework

Bud Craig’s work on interoception offers a much more realistic and applicable model for understanding pain:

Pain as a homeostatic emotion: Pain reflects disruptions in the body’s internal state, integrating interoceptive signals with emotional and cognitive processes.

Role of the insular cortex: Unlike the neuromatrix model, Craig’s framework emphasizes the insular cortex as a hub for processing interoceptive inputs (e.g., inflammation, fatigue) and driving adaptive responses.

Chronic pain as a prediction mismatch: Craig’s model explains chronic pain as a mismatch between the brain’s predictions and the body’s actual internal signals, a more accurate representation of what patients experience.

This framework doesn’t just make more sense scientifically—it aligns better with what patients and therapists see in the real world.

The unpleasantness of tonic pain is encoded by the insular cortex

While Moseley’s red/blue light study has been widely cited, its focus on acute skin-based sensations (exteroception) offers little relevance to the kind of pain most patients bring to a physiotherapist.

In stark contrast, Schreckenberger’s study, The unpleasantness of tonic pain is encoded by the insular cortex, dives into the mechanisms of interoceptive pain, the deep, internal discomfort often experienced in muscles and other tissues.

Schreckenberger’s research highlights how muscle pain—the type of pain patients commonly report—activates the insular cortex, which encodes the unpleasantness of pain tied to homeostatic dysregulation and internal states.

Unlike superficial findings from Moseley’s study, which rely on external cues like light, Schreckenberger’s work reflects real-world pain mechanisms and offers a far more valid framework for understanding and treating the persistent pain that drives patients to seek care.

This critical distinction underlines why Moseley’s study, despite its fame lacks practical relevance.

Time to Retire the Red/Blue Light Study

Moseley needs to stop using this study as the cornerstone of his arguments.

It’s outdated, oversimplified, and irrelevant to the complexity of chronic pain.

Pain science has moved on, and so should Moseley. His refusal to update his model—despite the clear limitations of this study—shows a troubling lack of humility.

The future of pain science lies in embracing complexity, not reducing pain to a “brain output” but understanding it as a dynamic interplay of interoception, homeostasis, and real-world biology.

Bud Craig’s interoceptive model offers a path forward.

Let’s stop relying on superficial lab studies and start focusing on what truly helps patients.

If Lorimer Mosely was open to question - this is what I would love to know…

"How do you see your red/blue light study, which focuses on external skin pain, applying to the deeper, internal pain that most patients experience in muscles or joints? And do you think its widespread interpretation might have unintentionally led to oversimplified treatments or left some patients feeling dismissed?"