This blog post was inspired by world leading sports scientist Tim Gabbett who recently posed the question,

Is it possible to develop an unbreakable athlete?

Tim elaborated on this on a recent podcast you can check out here.

My hope for this blog is that you may find something that resonates with you.

A (perhaps missing) piece that you can make part of your own unique and ever changing journey towards the holy grail of becoming an unbreakable athlete.

And if you think this article doesn't apply to you, in the words of Bill Bowerman,

"If you have a body you are an athlete".

The same principles apply for anyone who wants to break free of ongoing niggles and pain.

Be warned though, this blog is a long read, so get yourself a nice cuppa and get comfortable...

After studying the field of Physiotherapy for nearly 20 years now, I can say there’s no doubt that effective training is a blend of art and science.

There are a lot of opinions out there and it can be hard to figure out the right plan of attack.

In this blog I’ve tried to bring together the thoughts and opinions of world leading coaches, sport scientists and Physios and match it up with evidence based practice to help you achieve your goals.

We’ll try and put together a holistic and systematic approach that will develop a robust and resilient athlete, providing the foundation for planned training and competition.

I’ll also talk personally about some of the mistakes I’ve learned along the way.

Staying injury free

“The way to peak performance isn’t the secret, the secret is learning how to get to that point without getting injured along the way”

- Nick Willis dual Olympic medallist.

There is no one magical ‘correct’ way to train for everyone.

We all have our individual strengths, weaknesses, history and specific goals.

While we need to accept our approach will never be 100% perfect, we can always get better at it over the months and years.

Injuries are the number one factor limiting performance for athletes and the main obstacle holding you back from achieving your goals.

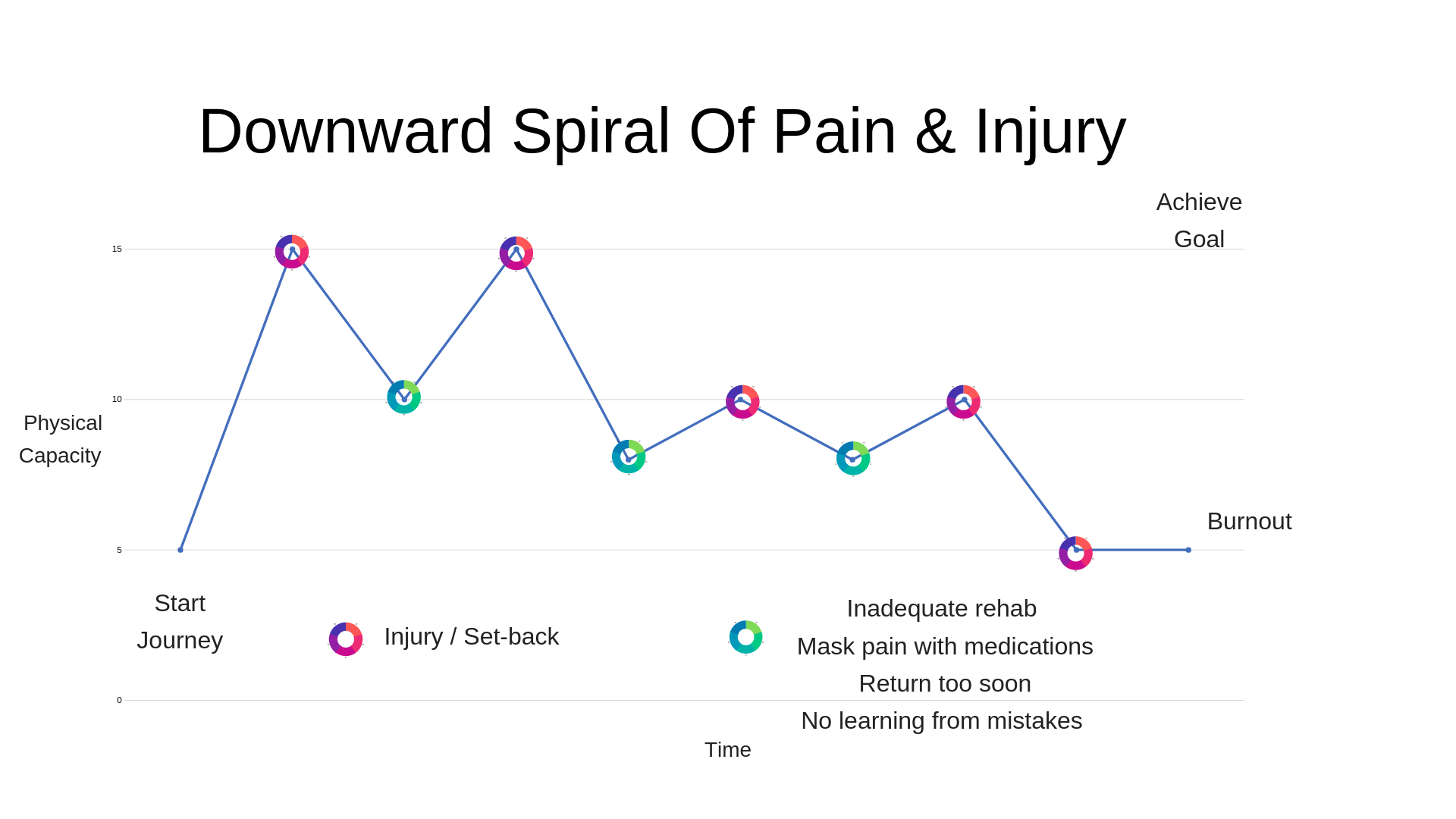

As well as reducing fitness dramatically, time off through injuries may also lead to weight gain and decreased physical capability, leading to a higher risk of future injury, sometimes leading to a downward spiral (See figure 1).

Ongoing injuries and time off training leads to an under-loading situation, and a perception of having a ‘vulnerable’ body that might break down at any stage.

Figure 1

Becoming An Unbreakable Athlete

On the other hand, if you can stay healthy for an extended period of time and put together some consistent weeks / months / years of training, improvement is virtually guaranteed.

Injury prevention needs to be a priority in your training plan with specific strategies in place (see below), otherwise you will break down sooner or later, especially as age catches up with you.

Really listening to your body and gaining self-knowledge about how you’re responding to your training and making appropriate adjustments to your schedule is what can make the difference between becoming an unbreakable athlete and ending up burnt out and not achieving your goals.

Addressing niggles / minor injuries early on and using a growth mindset can propel you towards becoming a resilient and robust athlete (see figure 2).

Figure 2

The ultimate cause of overuse injury

They say exercise is medicine and I agree with that.

But, you need to get the dose right. Too much or too little will lead to issues.

Research shows errors in load management are responsible for up to 75-80% of over-use injuries.

The perfect storm is when inadequate preparation (low physical capacity) meets with excessive training intensity and load (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Always keep this picture in mind !

Errors in load management can happen due to:

sudden excessive spikes in training load

over-training over time with insufficient recovery/adaptation

This is a recipe for disaster!

When your capacity is considerably lower than the demand placed upon it, your body remains in a constant state of stress and overload.

Injury is often a case of the straw that breaks the camels back, with signs and symptoms not heeded weeks or months beforehand.

There is a delicate balance between training and recovery and this can be difficult to achieve, especially if you are fueled by initial success and endorphin highs from challenging training sessions.

Unfortunately, in pursuit of gaining the competitive edge and high levels of internal motivation, injuries are very common.

Valuable time, energy and resources are then re-directed towards rehabilitating injured structures that can sometimes take weeks / months to heal properly.

As most older athletes can relate to, we can get stuck in a cycle of injury, pain and de-conditioning that can zap motivation quickly.

Sometimes it’s hard to see a way out when you’re stuck in the zone of stress.

Personally…

For me as a runner, I’ve experienced just about every injury and made all the mistakes about increasing training loads too quickly.

So I can very well understand your frustrations about your body.

You can go from practitioner to practitioner looking for a magic cure.

But until we can zoom out and see the bigger picture of why we’re getting injured, (grasping the capacity vs demand concept), we may never truly get over our niggling injuries.

As a Physio, I enjoy helping people with diagnosing and treating injuries.

But my real passion is to empower people to build their physical capacity to a point where they can create a ‘buffer zone’ where they can achieve their goals without risk or worry of becoming injured.

To see someone get out of chronic rehab and get back to their best, and restore their confidence in their bodies is hugely satisfying.

That is one of the reasons I created the KIN Foundation training system that helps build the fundamental movement skills as a crucial stepping stone to more lofty physical goals.

Key Point

A key point to be made here, is that it’s not the high demand and load that is generally the problem.

It’s how you go about preparing your body to handle that load.

Technically, you can build your capacity for any sort of demand, as long as you are well prepared for it.

An ultra marathoner who is well prepared for a 100km run may well have a lower risk of injury than a park runner doing their first 5km in 3 years.

I’m convinced it is possible to build an unbreakable athlete.

Let’s go into more detail…

5 Steps To Becoming An Unbreakable Athlete

1. Preparation

The first step in becoming an un-breakable athlete is to determine current physical capacity and know exactly where you’re heading.

If you’re a runner, you could do a 3km or 5km time trial that will determine your base aerobic capacity.

To assess your current musculo-skeletal capacity you could use the help of a Physio or Exercise Physiologist who would be able to guide through some testing.

With the help of a coach or physio, you can then use the feedback from your performance to structure a plan towards achieving your goal.

For example if you scored poorly on the aerobic test and felt out of breath really quickly - you’ll need to work on your cardio-respiratory fitness.

If you felt cramps or twinges in certain body parts - building specific structural capacity is what may be required.

Working closely with a Physio early on who can help you put together an indivdualised program can pay seriously big dividends later in your training program and avoid a lot of the issues of having things break down.

Preparing for the worst case scenario

A key part of becoming an unbreakable athlete is to identify the worst case demands on your body during competition.

For example, if you’re a runner with an upcoming race later in the year, you can break down the demands into more detail:

what is the exact distance?

what is the elevation profile - how many hills?

what sort of pace or time goal are you aiming for?

weather condition - hot, cold or windy?

what time of day will it start?

will it be crowded with people - are you used to running in big groups?

what time will the race start?

what is the transport like before the start?

what sort of nutrition and hydration is available on the course

To ensure your preparation is adequate, ‘begin with the end in mind’ and then start to train your body to be able to handle those specific loads.

Identifying the demands of running

To get more specific in terms of identifying the demands of running, I would say many people under-estimate the forces that are a placed on the body when you run.

Often there’s an assumption that running is a pretty natural form of exercise and that our bodies can easily handle it.

But when we look more closely, the figures can be a little disturbing.

The research shows, on average during the landing phase of the running cycle, we must absorb approximately three times body weight of force.

If we do a quick calculation - let’s say you weigh 70kg and go for a 10 km run (approximately 10,000 steps).

10,000 steps x 70kg x 3 times body weight = 2,100,000 kg of force

That is over 2 million kilograms of force your body needs to absorb, just for a 10km run.

You can see why many runners end up with a few niggles!

Running as a foundation for most sports

We know from the research that fatigue leads to higher injury rates and poor decision making capabilities.

We know of many world class golfers, tennis players and surfers who use running as their base foundation to improve their game and be able to compete with the best in the world.

If you play football, soccer or other sports - the demands will be specific to your position and your coach can give you more guidance as to training required.

In addition to running fitness, you may need to include strength, agility training and sport specific skills.

Keep in mind most AFL footballers and soccer players run around 10-15km in a game, so they need a huge aerobic foundation to be successful.

Most AFL clubs employ running coaches and exercise scientists to help prepare their athletes to compete at the highest level.

This blog post has a focus on running as it’s the foundation for most sports.

In fact running a half marathon (21km) can be one of the best barometers of your musculo-skeletal foundation.

2. Increase Capacity

The process of building your physical capacity to meet the demands of training and competition is known as load management.

On the face of it, preventing injuries should be pretty simple.

Just gradually increase capacity at a sensible rate until you meet (or even better exceed) the expected demands.

And sometimes this plan works smoothly, especially when you are young and robust.

Figure 4 below shows a fairly straightforward progression with the goal known as the ceiling and your current capacity as the floor.

Figure 4. Picture Credit: Tim Gabbett Training Injury Prevention Paradox Seminar

Things get more complex when you are attempting to build capacity and have some risk factors, such as:

history of injuries

low tissue capacity

poor general base fitness

inadequate nutritional support

lifestyle factors such as sitting or standing all day at work

mental / emotional stress

poor sleep

poor digestion

over-weight

older age

Your physical capacity may well have bottomed out and we call this being in the basement (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Picture Credit: Tim Gabbett Training Injury Prevention Paradox Seminar

You may be in the basement if you’ve:

had a long term injury and been unable to train

been inactive for many years and spent a lot of time sitting at work

recently been pregnant

had a flare-up of a chronic illness or recently had surgery

been on extended holiday

Getting from the basement to the ceiling is obviously going to be a longer, more difficult journey than if you started at the floor.

The other factor we have to consider is how much time you have to reach your goal.

The longer you have, the less likely you will be to spike your training loads and increase the risk of overload and causing injury.

Also it’s good to keep in mind that our body systems respond at different rates to training. For example cardio-respiratory fitness improves much faster than the muscuol-skeletal system (bones, muscles, tendons e.t.c) that may take months or years to fully develop.

Starting from the basement

If your current capacity is very low, it may be necessary to start with walking as your main form of aerobic exercise.

Walking is a seriously under-rated activity for athletes and especially runners.

If your goal is to eventually run a half marathon or marathon, walking has many benefits, particularly if you're coming back from an injury.

Here's 4 key benefits walking has for the runner:

✔️ Increases blood flow to aid recovery

✔️ Encourages gradual loading of tissues and creates a bridge to safely achieve higher loads of running

✔️ Helps maintain a healthy body weight

✔️ Mental benefits of staying active and achieving small wins & avoiding complete rest (that can dramatically drop your physical capacity)

If you can build your walking capacity to 30-40km per week, you will have an excellent foundation for layering in some running safely down the track.

Getting the foundation right

As you’re building capacity, there are three main variables in your training:

volume

frequency

intensity

If you imagine a sound mixing board with all the various levels you can adjust.

Obviously it would be unwise to increase all the channels at the same time.

For runners it’s fairly well accepted that your first priority is building your low-intensity volume and then layering in your speed and race specific training towards the end of your training cycle.

Some recent research from the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research has suggested that world-class long-distance running performances are best predicted by volume of easy runs (and deliberate practice of short-interval and tempo runs).

This novel study shows that there is a crucial role for long, easy runs that contribute to greater volumes of running, allowing for improved cardio-vascular efficiency (building a better engine) and optimal physiological functioning.

Arthur Lydiard the legendary New Zealand running coach strongly advised building this low-intensity aerobic base over a period of at least 3 months, (or 4-5 months if you’re starting out) and then building your race specific work later (see Figure 6).

Without the aerobic base, the more intense anaerobic training falls over and results become unpredictable.

The dramatic increase of injuries seen in team sports such as the AFL I believe can be traced back to players not getting significant component of endurance-based work in the pre-season.

Their bodies are put under enormous pressure with sprinting and high intensity drills placing extreme demands on them right from the early stages of their preparation.

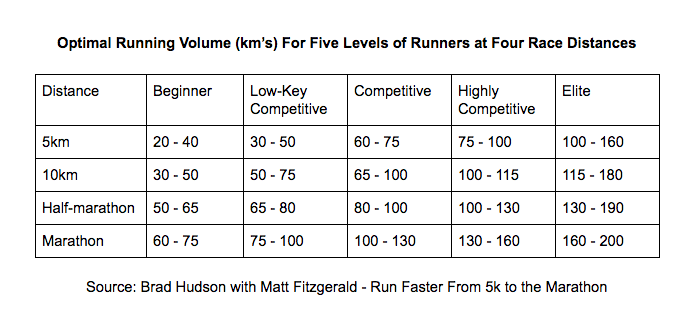

Building Your Optimal Running Volume

Figure 6 below gives you some guidance on your ideal weekly mileage to aim for (in kilometers), depending on your experience level and your running goals.

Figure 6.

Building higher volume initially will mean you’ll need to keep your intensity on the lower side.

To figure out what pace you should be doing your easy runs, we created an online calculator that can help you:

You can enter your most recent 3km or 5km time and see the pace range you should be aiming at for your easy runs.

It also gives you an accurate idea of your training zones for specific goals which is super handy.

Knowing and respecting your individual ‘easy’ zone pace (zone 1 and 2) is probably the single most important factor for a beginner runner to learn (see Figure 7).

Matt Fitzgerald has done a great job of explaining the finer points of getting your training intensity ratio right with his book 80:20 Running: Run Stronger and Race Faster By Training Slower.

Volume First, Speed Second

Here’s where Tim Gabbett’s training paradox comes into place.

Traditional thinking would suggest the more volume and training you do, the higher the ‘wear and tear’ on your body and the greater risk of injury.

This school of thought believes that training is important, but you’ve got to limit yourself, so you will be OK for competition.

However, the research is pretty clear that wrapping yourself in cotton wool from a training perspective leaves you unprepared to meet the demands of your sport, and opens your risk to developing an injury.

So hard and appropriate training is important - but you obviously can’t go out and give 110% in every training session.

Capacity must be built slowly by gradually expose yourself to higher demands.

Benefits of building low-intensity running volume base first

increase capillary density and mitochondria in muscles

improved running technique and efficiency - every stride is practice and improving your neuro-muscular efficiency

improves muscle strength and endurance

increases blood flow and circulation, leading to healthier tissues and aiding recovery

improves mind - body connection (can become aware of weak links early in the training cycle and strengthen them with a specific plan)

improves aerobic capacity, setting the foundation for the rest of the training to build upon

helps burn fat and maintain appropriate weight

Tips for building base mileage

think about getting more time on feet than achieving a certain pace

pace should be relaxed and easy - it should pass the ‘talk test’

keep your cadence relatively high, while maintaining a gentle pace (takes some practice)

insert walking breaks whenever you feel like you need it

keep your feet fresh by rotating between 2-3 of running shoes

get onto the trails where you can take some pressure off your joints and enjoy being out in nature

listen to running podcasts…highly recommend the Inside Running Podcast

Discovering your weak links

Most of us have some weak links in our body that we may never know until we start to increase demand.

As you’re progressing in training, the harder sessions will ‘test’ your physical capacity and movement foundation.

The benefit of building your low-intensity volume in the initial few months of training is that it can expose weak links in your body, without risking huge strain on your body.

Because there is no pressure to be fast and progress too quickly, in this phase you can take your time to properly address the issue.

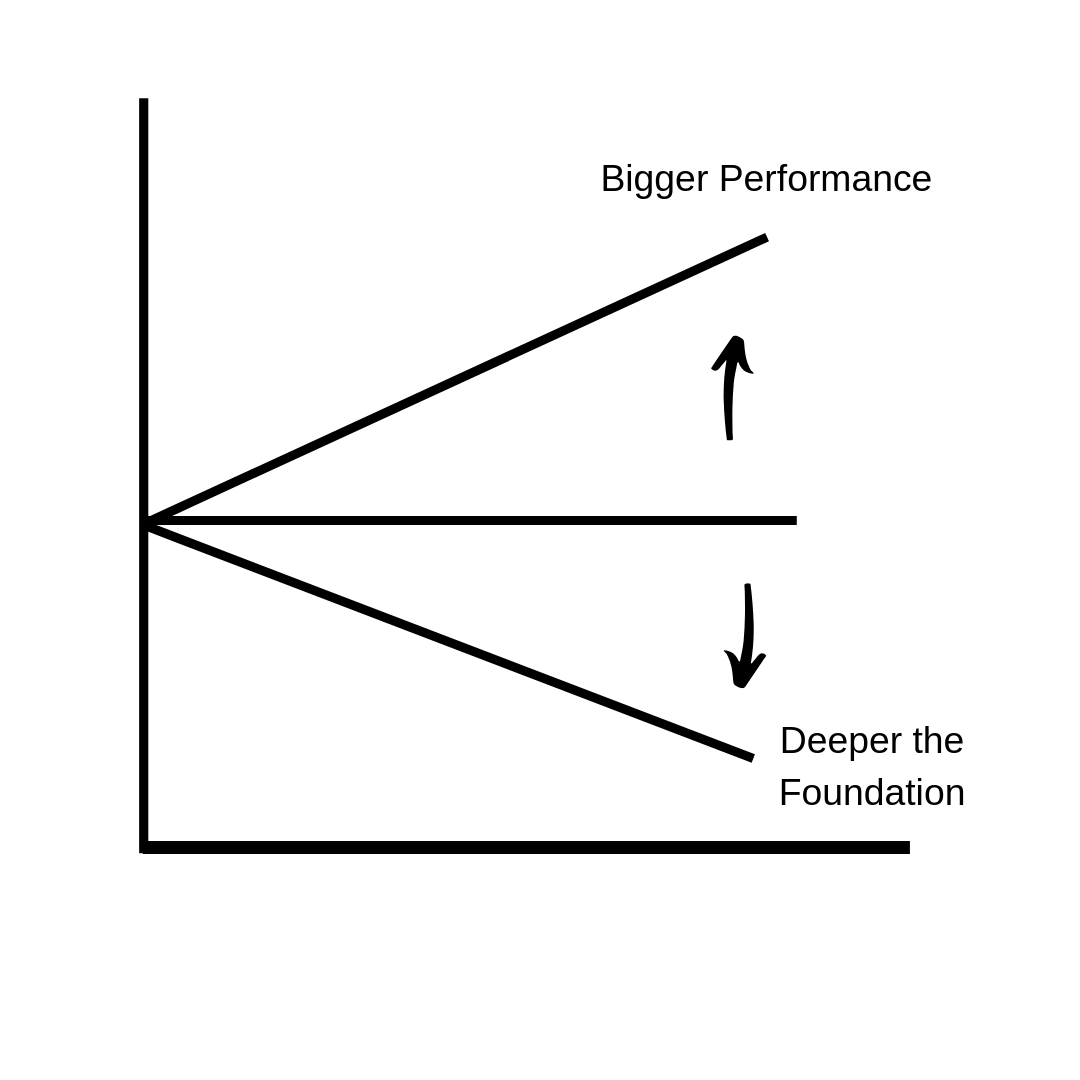

Figure 8

The bigger the upcoming performance, the deeper your foundation has to run to support the demands (See below Figure 8).

Identifying your weak links can sometimes be really easy - it’s the area of your body that is overloaded and painful.

But there is often also a deeper root cause of why a certain tissue is getting overloaded.

That is where a good Physio can help you do some detective work and identify the more subtle biomechanical issues that may be contributing.

These issues may be things like:

weak or inefficient core muscles

inactive glutes

stiff ankles from past injury

tight hip flexors

poor body awareness

Won’t all this easy running make me slow?

For many years I followed more of a high threshold training approach, believing that training at the pace you want to race at would stimulate the most beneficial training gains.

As a younger athlete with good recovery powers, this seemed to work well.

I did throw in some occasional slower runs, but to be honest I felt guilty doing them because it felt like going slow was completely counter-productive and my body would become soft.

As I have gotten older though, things changed. Harder training sessions took more of a toll and recovery was not as good as it was when I was young.

The old ego was not allowing me to get the proper training that I needed.

It wasn’t until I had a good discussion with running coach / podiatrist Michael Nitschke and he showed me this graph of the training intensity ratios of elite runners.

This was a really good wake up call.

The 80/20 principle of training came into full realization.

Once I fully accepted this principle, a weight was really lifted off my shoulders.

Suddenly I had the green light to run easy, and not feel guilty!

I distinctly remember my first conscious effort to run along at an easy pace.

It was really hard to slow down and be disciplined.

But after about 10 minutes I got over that and then started thinking - this so much fun!

Running suddenly turned into a pleasurable activity, when I wasn’t picking up the pace and burning out with fatigue on every run.

Admittedly the results of this approach to took a little longer to appear.

The ego and running pace takes a short-term hit.

But 6-12 months later, a solid foundation had built up from which faster running will come.

Invest in your training and reap the dividends

To use an analogy, running is like how you manage your money.

Easy running / building up high volume is like building your savings.

Every time you can go out for a jog without pushing into your red zone / high intensity, you’re building up your account.

Every minute your working hard above your threshold you’re spending money.

If you spend more than you save, you’ll go into debt pretty quickly and the bank will call you up and demand you start paying back what you owe.

Injuries are like going into debt.

If you can be disciplined and sensible, investing your savings over time (building your low-intensity volume) over many months and years, you’ll get to really enjoying spending the dividends on race day.

“The less effort, the faster and more powerful you will be” - Lao-tze

Efficient vs Effective Training - The tortoise and the hare

In terms of producing short-term results, there’s no doubt doing threshold runs and pushing your intensity gets you fit and ensures rapid progression towards your goal.

In terms of time invested vs results, this is a highly efficient way to train.

But because each week is full of hard training, it means there is a limit to how much capacity you can generate as you need to allow for rest and recovery.

Your improvement will be quick in the beginning but will begin to plateau fairly quickly.

As your fitness reaches as a plateau, improvements can be smaller, and because of this the temptation is to push even harder in training, naturally leading to an increased injury risk.

On the other hand, effective training, as proposed by Lydiard, recommends more of a pyramid training approach, with the emphasis on increasing total capacity (achieving higher volume mileage) in the beginning of a training cycle.

By starting off slowly and gradually building up can possibly yield better results in the long-term.

The story of the tortoise and could be analagous to the training styles.

As stated above, there is no one ‘right’ way to train for everyone and the research is still lacking.

The important thing is to listen to your body and if somethings working well that stick with it.

But if you’re having ongoing niggles or have plataued in your training, you may need to re-assess your training approach.