Building Capacity - How Hard Is It, Really?

Getting fitter and stronger involves a very simple equation:

Stress + Rest = Adaptation

On the face of it, as you build up your training, progress should be fairly linear, right?

For example, let’s say your training for your first marathon.

You start off with 5km runs which are very manageable, build up to 10km which your body enjoys and then 15km is a bit of stretch. When you get into the 20km+ long runs - all of a sudden something goes wrong…a niggle.

All of a sudden your perfectly laid out training plan is looking a little shaky.

You need time off, but that means while you rest your injury, your fitness is going backwards.

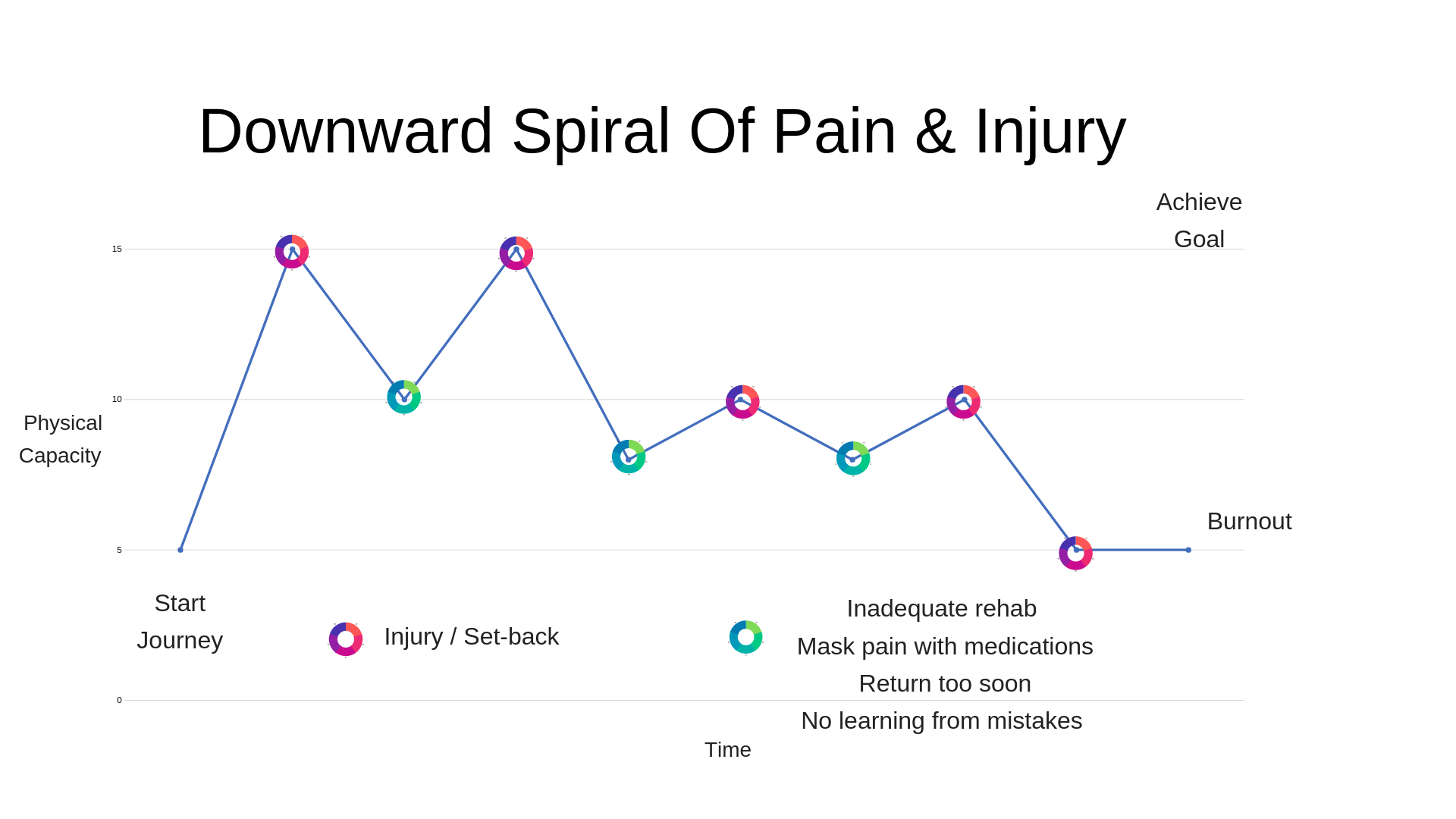

Instead of picture graph A below, your training turns into graph B (thanks to Adam Meakins for the graph).

The goal of this blog is to help make your climb as smooth as possible - no doubt there will still be ups and downs. This makes life interesting and reaching your goals even more satisfying.

But if we can avoid the dramatic boom-bust cycle in your training, I think you would enjoy the process much more.

As Matt Fitzgerald writes in his book RUN: The Mind-Body Method of Running by Feel, developing confidence in your body through sensible and effective training, leads to an upward spiral of enjoyment, satisfaction and ultimately improved performance.

Monitor Training Loads

“If you can’t measure it you can’t manage it”

There are many variables in how you apply a load and how you measure it.

So in the blog we’re going to take a look at the bigger picture of training loads, as well as zooming down to the daily battle of improving fitness.

The first step to avoiding the boom and bust cycle is becoming aware of your training load.

You can test the seriousness of an athlete by the presence of the wearable technology they use, with beginners relying on feel or an app.

With increased interest in progressing your training, the next step is investing in a GPS Running Watch.

With a GPS watch you can collect data such as:

Distance

Time

Current Pace

Average Pace

Splits

Cadence

Heart Rate

Estimated VO2 Max

Without a GPS watch, the research shows athletes are traditionally quite poor at measuring their training load.

For example, a recent paper shows athletes with bone stress injuries, tended to under-report their training volume.

We learnt from blog post 1 that many of us, especially beginners, under-appreciate the demands that running places on our body, and subsequently go onto cause damage and injury.

You can’t blame the activity

Often, when injury happens, we can be quick to blame the activity itself - believing it is dangerous and best to avoid it.

This can lead to a downward spiral of reduced fitness and lowered tissue resilience, further increasing the risk of injury.

No doubt this is how running probably got a bad rap and why your ill-informed relative continues to insist that running is wrecking your knees (it isn’t).

Instead of worrying about local tissue damage and pathology (aside from accidents), we can simply modify the load we are placing on ourselves, as this arguably has a greater influence on recovery more than any other factor.

As humans, we have bodies that are more like gardens that, given the right conditions, flourish and thrive, and once or twice per year give off the fruits and rewards of our labour.

Unlike a car, that tends to wear out with use - we are adaptable and actually thrive when given the right amount of positive challenge / stimuli.

Taking this view, we can see our injuries and niggles in through a wider lens.

If we understand how the various training loads affects us, we are less likely to be worried when the aches and pains strike.

We’ll talk more about that later.

For now, a quick story…

Getting your training recipe right

Admittedly, I am terrible at baking.

A few years ago I found this delicious cookie recipe.

I used to make it for our hikes and when I pulled them out on our breaks and got a Masterchef worthy applause from friends and family.

But then something odd happened…they started testing terrible!

Maybe because I have 2 kids now and I’m rushing around a bit more, so when I go to throw the ingredients in, I’m a bit more haphazard.

After a few more tries, they continued to taste even worse.

I finally had a good chat with my wife about why they tasted so bad, and I realized I had been adding waaaayyy to much bi-carb soda.

For some odd reason, instead of the half teaspoon that the recipe called for, I had got into the habit of grabbing the box and pouring some in, without measuring it…obviously way too much, so the cookies came out tasting weird and bitter.

In my head, I knew when baking it was important to measure things (my wife is a big stickler for that)…but subconsciously I was like,

“A little bit is good, so more must be better right?”

So I had wrecked the cookies by accidentally adding too much of one element and the balance of flavours was completely off and impossible to enjoy.

I think running can be like cooking.

You have all your ingredients and if you focus on getting the balance right - you will have a successful time achieving your goals and your enjoyment will sky rocket.

On the other hand, get the balance wrong, and your body will soon tell you.

When you look at experienced chefs - they are continously tasting their cooking - and modifying and adapting as they go to produce the best result.

But we need a way of measuring, otherwise there will a tendency to stuff things up, just like I did with the cookies.

The great thing about training is you can mix in the ingredients as you like, put it in the oven, and see what comes out on race day.

There are so many options and variables that everyone has their own unique blend.

But once you find a good recipe you stick to it.

Won’t looking at my numbers take away the fun of running?

I know there are some purists out there who resist the notion of monitoring their training.

I completely understand and I think there is a real risk of getting distracted/addicted to your watch and losing the connection to how you’re feeling and enjoying being in the moment with what’s going on around you.

But if you are always injured, or not achieving the goals you set out to achieve, then to me, that is worthy of further investigation of your training habits.

Running by intuition can play an important role in a balanced program (see below) - but sometimes it can be completely off.

The best example is someone who’s results have plateaued, and their intuition tells them they simply need to push themselves harder and harder in training. They may even feel like they are mentally weak.

In reality, they be simply over-trained and exhausted due to an un-monitored and overly demanding training program.

Imagine if you were to buy a lamborghini - that is incredibly powerful - but it didn’t come with a speedometer. The risk of speeding and getting yourself a ticket would be fairly high.

Investing a small amount of energy into monitoring your training ultimately should lead to less injuries - which means more time and enjoyment from the sport.

And you should be able to run happily as long as you want to into old-age.

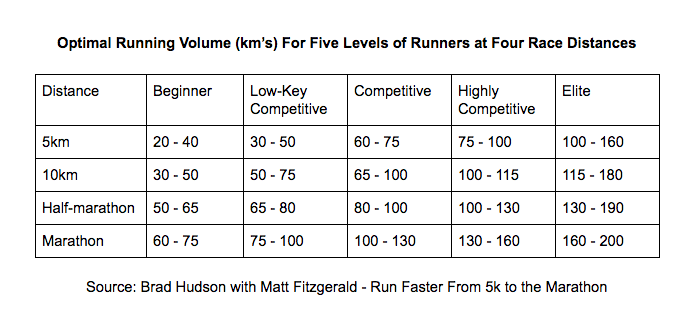

Finding your optimal training

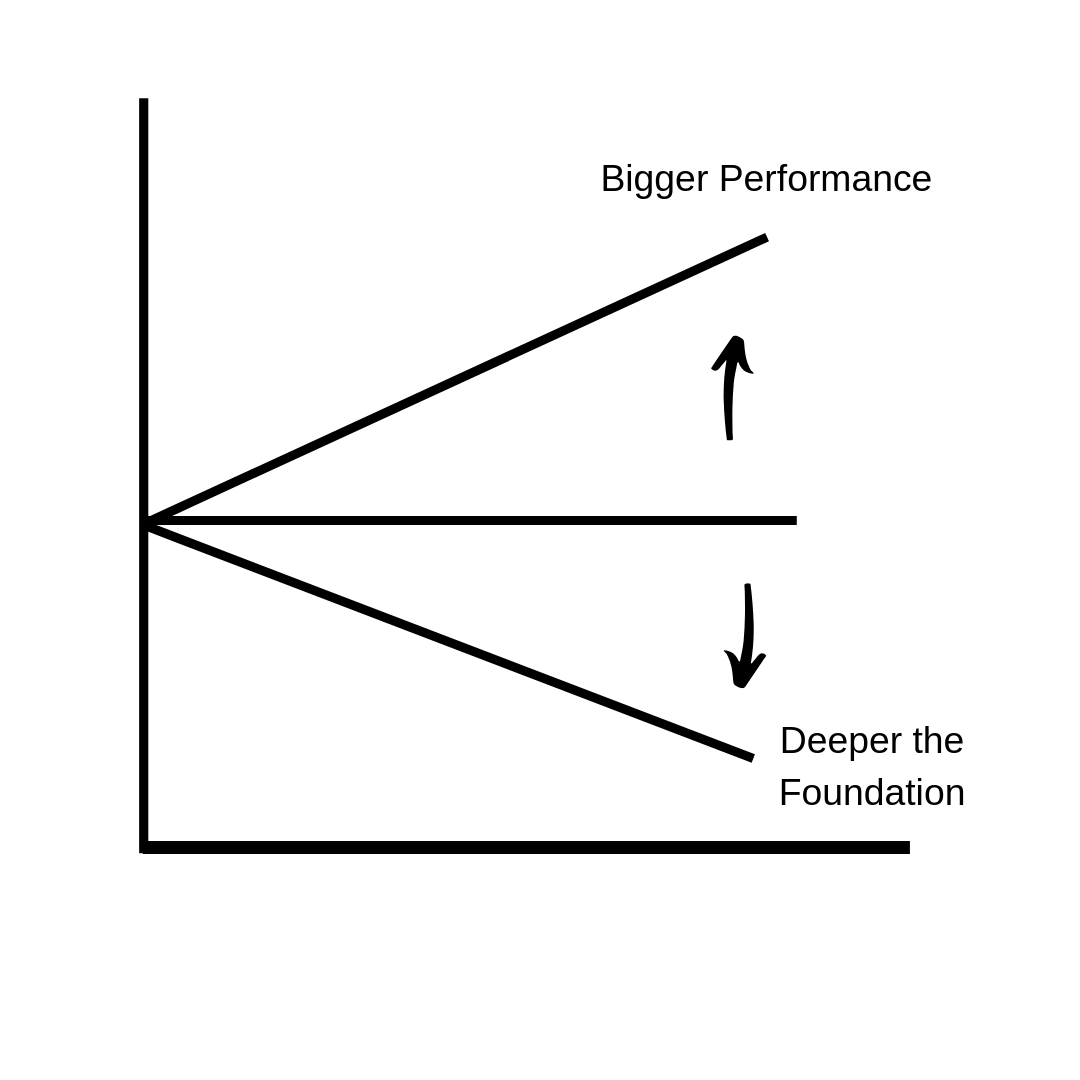

The graph below shows the relationship between training load and optimal performance.

The ideal training stimulus ‘sweet spot’ is the zone between improving fitness and building physical capacity, while at the same time limiting the negative consequences of training (ie, injury, illness, fatigue and overtraining).

Both under-training and over-training will lead to poor performance.

As you progress your training, your body will have the ability to absorb greater training loads.

Finding that sweet spot can be a little tricky, so how could monitoring our training load help us?

10% Rule

For many years athletes have used the 10% rule to guide their training - that is to never increase training load more than 10% on a week to week basis.

This has worked well for many athletes as a general guide, especially during the mid-phase of a training program.

But for athletes just starting out the 10% rule would probably be too slow of a build-up and athletes who are already at their peak it would be too much of an increase.

See the bigger picture of your training load

Another strategy, popularized by sports scientist Tim Gabbett is to use a ratio that compares your short term training (typically measured over a week) with your base fitness (typically measured as the average weekly load over the past month).

This is know as the acute:chronic load ratio.

For example if you run an average of 50km per week over the past month and the next week in your training cycle, you cover another 50km, the ratio would be:

Acute 50km (most recent week) : Chronic 50km (average over the past 4 weeks) —> 50 divided by 50 = 1

A score of 1 means your fitness will remain pretty stable, with a very low chance of injury (see graph below).

If you increase your subsequent week to 60km - the ratio would be:

Acute 60km : Chronic 50km —> 60 divided by 50 = 1.3

Tim Gabbett’s extensive work has suggested that a ratio of 0.8 - 1.3 is generally sustainable and is the ‘sweet spot’ for optimal training (see graph below).

But as your ratio gets up 1.5 or higher, your risk of injury increases.