Creating An Unbreakable Athlete Part 2 (Monitoring and Adapting).

This is part two of a three part series about building an ‘unbreakable athlete’.

The three parts consist of:

Identifying the Peak Demands of Your Sport and Building Capacity

Monitoring and Adapting your Training

Recovery

As mentioned in Part 1, there is no one ‘right’ way to train for everyone.

This blog is an attempt to set out some basic principles you can use as a guide and then you can mold it with your own unique flavour.

The important thing is to listen to your body and if something’s working well that stick with it.

But if you’re having ongoing niggles or have plataued in your training, you may need to re-assess your training approach.

As always, this blog contains very general information and should be used in conjunction with a coach or health care professional.

Also, as most sports have running as their base, we are once again focusing on how to build your capacity for running, as it is the foundation for everything else.

A small warning, half way through this blog we go down some deep rabbit holes in terms of monitoring the numbers.

If you happen to be a numbers person you will appreciate it, but if not, just skip that section and think about the overall principles instead.

Building Capacity - How Hard Is It, Really?

Getting fitter and stronger involves a very simple equation:

Stress + Rest = Adaptation

On the face of it, as you build up your training, progress should be fairly linear, right?

For example, let’s say your training for your first marathon.

You start off with 5km runs which are very manageable, build up to 10km which your body enjoys and then 15km is a bit of stretch. When you get into the 20km+ long runs - all of a sudden something goes wrong…a niggle.

All of a sudden your perfectly laid out training plan is looking a little shaky.

You need time off, but that means while you rest your injury, your fitness is going backwards.

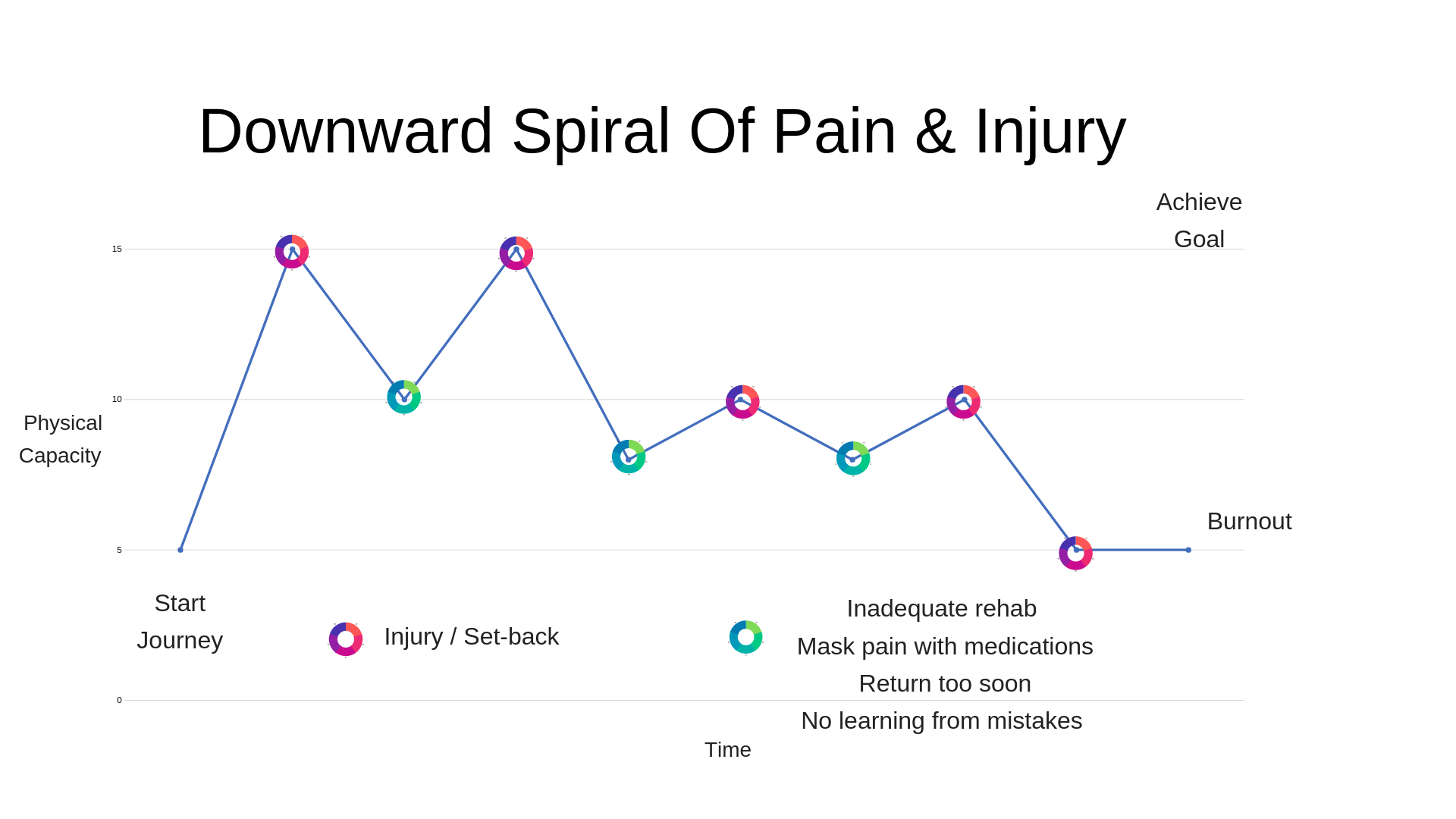

Instead of picture graph A below, your training turns into graph B (thanks to Adam Meakins for the graph).

The goal of this blog is to help make your climb as smooth as possible - no doubt there will still be ups and downs. This makes life interesting and reaching your goals even more satisfying.

But if we can avoid the dramatic boom-bust cycle in your training, I think you would enjoy the process much more.

As Matt Fitzgerald writes in his book RUN: The Mind-Body Method of Running by Feel, developing confidence in your body through sensible and effective training, leads to an upward spiral of enjoyment, satisfaction and ultimately improved performance.

Monitor Training Loads

“If you can’t measure it you can’t manage it”

There are many variables in how you apply a load and how you measure it.

So in the blog we’re going to take a look at the bigger picture of training loads, as well as zooming down to the daily battle of improving fitness.

The first step to avoiding the boom and bust cycle is becoming aware of your training load.

You can test the seriousness of an athlete by the presence of the wearable technology they use, with beginners relying on feel or an app.

With increased interest in progressing your training, the next step is investing in a GPS Running Watch.

With a GPS watch you can collect data such as:

Distance

Time

Current Pace

Average Pace

Splits

Cadence

Heart Rate

Estimated VO2 Max

Without a GPS watch, the research shows athletes are traditionally quite poor at measuring their training load.

For example, a recent paper shows athletes with bone stress injuries, tended to under-report their training volume.

We learnt from blog post 1 that many of us, especially beginners, under-appreciate the demands that running places on our body, and subsequently go onto cause damage and injury.

You can’t blame the activity

Often, when injury happens, we can be quick to blame the activity itself - believing it is dangerous and best to avoid it.

This can lead to a downward spiral of reduced fitness and lowered tissue resilience, further increasing the risk of injury.

No doubt this is how running probably got a bad rap and why your ill-informed relative continues to insist that running is wrecking your knees (it isn’t).

Instead of worrying about local tissue damage and pathology (aside from accidents), we can simply modify the load we are placing on ourselves, as this arguably has a greater influence on recovery more than any other factor.

As humans, we have bodies that are more like gardens that, given the right conditions, flourish and thrive, and once or twice per year give off the fruits and rewards of our labour.

Unlike a car, that tends to wear out with use - we are adaptable and actually thrive when given the right amount of positive challenge / stimuli.

Taking this view, we can see our injuries and niggles in through a wider lens.

If we understand how the various training loads affects us, we are less likely to be worried when the aches and pains strike.

We’ll talk more about that later.

For now, a quick story…

Getting your training recipe right

Admittedly, I am terrible at baking.

A few years ago I found this delicious cookie recipe.

I used to make it for our hikes and when I pulled them out on our breaks and got a Masterchef worthy applause from friends and family.

But then something odd happened…they started testing terrible!

Maybe because I have 2 kids now and I’m rushing around a bit more, so when I go to throw the ingredients in, I’m a bit more haphazard.

After a few more tries, they continued to taste even worse.

I finally had a good chat with my wife about why they tasted so bad, and I realized I had been adding waaaayyy to much bi-carb soda.

For some odd reason, instead of the half teaspoon that the recipe called for, I had got into the habit of grabbing the box and pouring some in, without measuring it…obviously way too much, so the cookies came out tasting weird and bitter.

In my head, I knew when baking it was important to measure things (my wife is a big stickler for that)…but subconsciously I was like,

“A little bit is good, so more must be better right?”

So I had wrecked the cookies by accidentally adding too much of one element and the balance of flavours was completely off and impossible to enjoy.

I think running can be like cooking.

You have all your ingredients and if you focus on getting the balance right - you will have a successful time achieving your goals and your enjoyment will sky rocket.

On the other hand, get the balance wrong, and your body will soon tell you.

When you look at experienced chefs - they are continously tasting their cooking - and modifying and adapting as they go to produce the best result.

But we need a way of measuring, otherwise there will a tendency to stuff things up, just like I did with the cookies.

The great thing about training is you can mix in the ingredients as you like, put it in the oven, and see what comes out on race day.

There are so many options and variables that everyone has their own unique blend.

But once you find a good recipe you stick to it.

Won’t looking at my numbers take away the fun of running?

I know there are some purists out there who resist the notion of monitoring their training.

I completely understand and I think there is a real risk of getting distracted/addicted to your watch and losing the connection to how you’re feeling and enjoying being in the moment with what’s going on around you.

But if you are always injured, or not achieving the goals you set out to achieve, then to me, that is worthy of further investigation of your training habits.

Running by intuition can play an important role in a balanced program (see below) - but sometimes it can be completely off.

The best example is someone who’s results have plateaued, and their intuition tells them they simply need to push themselves harder and harder in training. They may even feel like they are mentally weak.

In reality, they be simply over-trained and exhausted due to an un-monitored and overly demanding training program.

Imagine if you were to buy a lamborghini - that is incredibly powerful - but it didn’t come with a speedometer. The risk of speeding and getting yourself a ticket would be fairly high.

Investing a small amount of energy into monitoring your training ultimately should lead to less injuries - which means more time and enjoyment from the sport.

And you should be able to run happily as long as you want to into old-age.

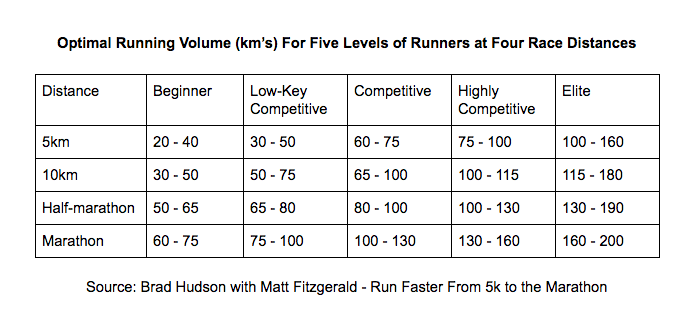

Finding your optimal training

The graph below shows the relationship between training load and optimal performance.

The ideal training stimulus ‘sweet spot’ is the zone between improving fitness and building physical capacity, while at the same time limiting the negative consequences of training (ie, injury, illness, fatigue and overtraining).

Both under-training and over-training will lead to poor performance.

As you progress your training, your body will have the ability to absorb greater training loads.

Finding that sweet spot can be a little tricky, so how could monitoring our training load help us?

10% Rule

For many years athletes have used the 10% rule to guide their training - that is to never increase training load more than 10% on a week to week basis.

This has worked well for many athletes as a general guide, especially during the mid-phase of a training program.

But for athletes just starting out the 10% rule would probably be too slow of a build-up and athletes who are already at their peak it would be too much of an increase.

See the bigger picture of your training load

Another strategy, popularized by sports scientist Tim Gabbett is to use a ratio that compares your short term training (typically measured over a week) with your base fitness (typically measured as the average weekly load over the past month).

This is know as the acute:chronic load ratio.

For example if you run an average of 50km per week over the past month and the next week in your training cycle, you cover another 50km, the ratio would be:

Acute 50km (most recent week) : Chronic 50km (average over the past 4 weeks) —> 50 divided by 50 = 1

A score of 1 means your fitness will remain pretty stable, with a very low chance of injury (see graph below).

If you increase your subsequent week to 60km - the ratio would be:

Acute 60km : Chronic 50km —> 60 divided by 50 = 1.3

Tim Gabbett’s extensive work has suggested that a ratio of 0.8 - 1.3 is generally sustainable and is the ‘sweet spot’ for optimal training (see graph below).

But as your ratio gets up 1.5 or higher, your risk of injury increases.

Spikes in training loads are necessary to improve fitness, but spikes that are too great can lead to an increased risk of injury (see pic below).

Excessive spikes in training load normally relate to a sudden increase in volume or intensity.

Often this can happen after a period of reduced activity e.g. coming back from an injury or at the start of pre-season after a holiday.

It can also be related to sudden decrease in your bodies capacity relative to your training loads e.g. high emotional / environmental stress, poor quality sleep, nutritional / digestive issues, serious illness, poor recovery strategies) that increase the chances of an injury developing.

We know that not every time you spike your training load you will get injured, as some athletes are more robust than others. This ratio just gives us a general guide about the increased possibility of injury. Being aware of when your training load is high, you have the advantage of really doubling down on your recovery (sleep, nutrition and maintaining tissue quality) to help absorb to higher demands of training.

We will go into more detail later about some of the factors that influence your likelihood of getting injured, and how you can modify your training to avoid time on the sideline.

Benefit of the acute:chronic ratio

The acute:chronic workload ratio is considered a ‘best practice’ approach to monitor athlete workloads. As stated above, an acute: chronic workload ratio of ≥1.5 has been associated with large increases in injury risk.

The benefit of keeping an eye on the acute:chronic ratio is that is really emphasizes keeping your consistent base training volume relatively stable.

This means you can afford to spike your training loads in order to improve fitness, without increasing the risk of injury.

It’s a rather technical way of monitoring your load and ensuring a safe transition to higher physical capacity.

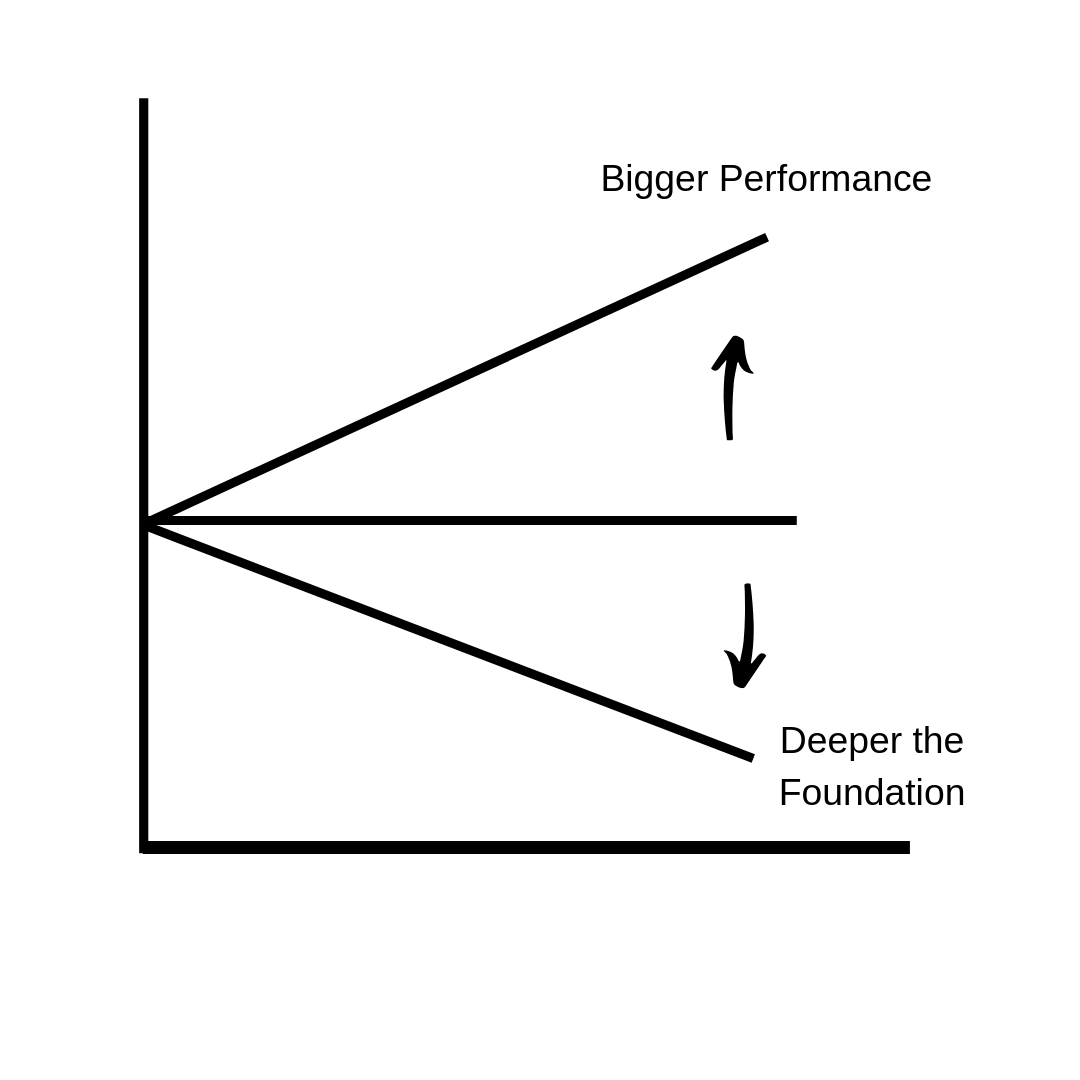

To become an unbreakable athlete, it definitely helps if you’re not in a rush.

Veteran marathoners and experienced coaches advise it may take 5-10 years to really realize your full potential as a runner / athlete, and building this chronic capacity is what they are alluding to.

How to find your chronic ratio

If you have a Garmin GPS watch, a simple and quick way of monitoring this acute: chronic ratio is to view your ‘Activities’ and check your 4 week average (see Figure below).

On the bottom left hand corner you will see your average distance over the past 4 weeks.

One of the most important metrics you can track (Bottom left hand corner) - Average Weekly Km over the past 4 weeks. This is know as your Chronic Load and is a measure of your general fitness. A good idea to check this number before your plan you upcoming training week.

To be sure you’re not over-training and increasing the risk of injury - your upcoming training weekly should be between 0.8 and 1.3.

Spikes of 1.5 or more may be tolerated, but do increase your injury risk and you’d need to really put a lot of effort into recovery.

Getting more specific with monitoring load

Another important point - obviously measuring distance covered alone doesn’t tell the full story about your training loads.

A 50km week of intense threshold training is very different to 50km of easy jogging.

If you follow the 80:20 principle (80% of your training easy, 20% hard) as proposed by Matt Fitzgerald, then using your Garmin’s distance would give you a good general guide about how much load you are getting each week.

The other option, more specific way is to use a Rate of Perceived Exertion Scale (RPE) and combine it with your training minutes.

So for every training session, you rate it on a scale of 0-10, where 10 is the hardest.

Then you would multiply the minutes trained with your RPE score to get the more accurate training load number.

E.g. you did a hard run at 60 mins

60 mins x 8 RPE = 400 units of load in that training session.

Using the acute:chronic training ratio over the course of weeks and months here would be highly specific, but obviously quite time consuming for the average runner and probably more for those wanting to take things more seriously.

There are some spreadsheets available online, also using Strava’s premium monitoring can give some good data that helps track your intensity and workload.

Coming back from injury / illness / time off running

We know from the research - the biggest risk for an injury is a past injury - meaning the way we return to our chosen sport is often not ideal.

Arguably the reason many athletes suffer injury after injury, could well be the way we manage their load upon return.

For example, let’s say you’ve averaged 50km per week over the past 4 weeks, and your training is going great in the build up to your next race.

Your chronic load is 50km, meaning a spike in load up 1.3 x 50 would be probably be OK.

That means your following week’s training, you have some extra time and want to build some volume, so you can (everything else being equal) build up to 65km in the week.

On the other hand, let’s say you come down with the flu, or happen to sustain an injury meaning you have 2 full weeks off running.

The last 4 weeks all of a sudden looks a little different:

Chronic Load Calculation:

50 + 50 + 0 + 0 = 100

100 divided by 4 weeks = Chronic Load of 25

So that crucial first week after your break - you may be anxious to get back to running and you return your standard 50km week (or even try and make up for lost time by doing a 65km week).

Acute to Chronic Load Calculation:

50 divided by 25 = 2 - which puts you at a dramatically higher risk of further injury.

Once again, going by the acute:chronic load calculator - increases of up to x 1.3 are generally safe.

In this example, the runner would have been wise to limit their first week back to a much more manageable 25km- 32.5km.

Just to confuse you a little more, injuries don’t peak until 3-6 weeks after training errors take place, so keeping accurate training data becomes even more vital.

Take home message

The key message here is the higher your consistent monthly average, the more you license you have to spike your load safely, in preparation for your specific upcoming event.

If you regularly miss days or weeks of training and you try and make up for it with higher intensity sessions, you may be setting yourself up for a frustrating boom-bust cycle of injury - where you have high physical fitness, but your body is continually breaking down, from one injury to the next.

Before you plan your training week, have a quick check of your average weekly load over the past 4 weeks, and make your decisions from there.

This approach will test your patience and it requires some faith in the science, as well as your body’s ability to adapt.

The slower, more considered return to running will pay dividends weeks and months later when you have made a successful return to training and running.

Training Guidelines

If we look at top world class runners, they schedule 2-3 hard sessions maximum per week where they are really pushing themselves.

The rest of their training (80%) is spent at easy intensities, focusing on building their volume and efficiency.

Other training tips include:

Consistency in training trumps short-term intensity

Allow a proper warm-up and cool down. Your warm-up may involve some foam rolling and gluteal / core engager exercises (especially if you sit a lot of the day) to prepare your body for optimal performance

Schedule a rest day at least once per week, or 2-3 days per week if your a beginner

Never do two very hard training days back to back (unless you are very experienced)

Take a recovery week every third or fourth week to consolidate the training you’ve done and keep you fresh and motivated for the next training cycle

Build your low intensity base volume early in the season and then focus on speed work later

Saves the long hill runs for later in your training program, but you can include short hill sprints (e.g. 10 x 10 secs) early in your program to help build leg strength

Increasing Training Loads - What To Look Out For

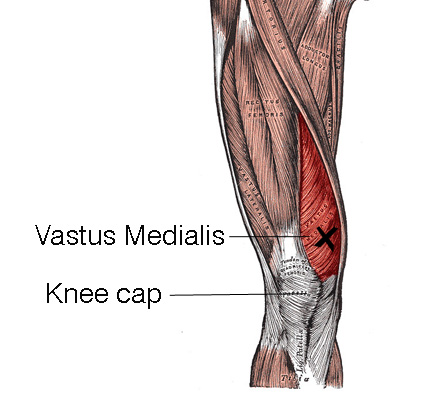

As you start increasing your training load, certain tissues have a tendency to become overloaded.

The following graph gives an excellent visual of the common issues many runners face.

Photo Credit: Rich Wily Running Symposium La Trobe 2018

If you are doing a lot of ‘speed work’ - your calf, plantar fascia and achilles is at high risk. Tendon soreness/pain can often take 24 - 72 hours after sessions to fully come on, so that is something to be aware of as you plan your week.

If you are doing more higher volume work - your knee, tibia and lower limb stress injuries are more prevalent.

If you have a history of certain injuries, it may be worthwhile avoiding excess speed or volume work in the short-term until you have built up a better base foundation.

Signs of over-training:

Sometimes we can push our training too far and I think most athletes have had the feeling that comes from over-training.

It’s normal to be fatigued and sore, but there are some other signs that can point towards over-training such as:

Lack of enjoyment in training and racing

Un-explainable under-performance

Persistent, extreme fatigue

Increased sense of effort in training

Sleep disorders

Fluctuating mood

Listening can be hard

It can be hard for runners to listen to their bodies as pain killing hormones such as endorphins can mask the damage.

Ignoring and going into denial early on and turn small niggles into serious injuries.

Sometimes you need to hit rock bottom i.e. you can’t run or train at all due to pain and weakness, before you change your approach.

Monitoring Tissue Quality

The state of your musculo-skeletal system is generally a pretty good predictor of the state of your body’s readiness to perform.

Improving body awareness through things like massage, foam rolling, stretching, yoga and stretching can give you an early sign that your tissues may not be handling the loads of your training.

As a Physio, I spent a lot of my time ‘panel beating’ tight muscles and get a sense of whether a tissue is abnormally tight. If appropriate we can perform a series of treatments, over time noticing the tissues moving towards a better state of equilibrium.

More importantly, I can give feedback to the client about extra self-care they may need to focus on, teaching people more about potential ‘blind spots’ they have e.g. hidden tight spots, under-active muscle firing or an inefficient movement pattern that could increase injury risk and limit performance.

If you are ‘tight everywhere’ which many athletes complain of - it’s most likely a training overload situation and no amount of foam rolling or needling will help until you address the underlying cause - so the reason for this blog series.

Injuries

Warning signs that you have an injury may include:

intense pain > 5/10

night pain

excess swelling and inflammation

pain that gets worse with exercise or 24-48 hours following exercise

The most important way to avoid injuries is to not train through pain.

If you are feeling pain from an injury, it is wise to take 3 days off running, then have 2-3 days of low intensity running to see how it responds.

Getting into to see your local Physio early on can also be a big help in getting the best treatment and plan in place.

Intuitive - Running by Feel

As you become more experienced as an athlete, you learn to trust what your body is telling you on a day to day basis and make adjustments to your program.

Listening to your body over time will help you to define your optimal training formula in terms of the volume and intensity of your training.

I’m a big believer that getting out there and running more is the best teacher. Intuition is a great guide - and your body is always talking to you and giving you hints and tips about what it needs.

The other thing to keep in mind is that when you’re feeling good - it can often be hard to know when to call it quits on a session as there is a temptation to push that little bit extra in the hope of gaining that extra bit of fitness.

Bradley Croker, co-host of the Inside Running Podcast summed it up perfectly, when he was reflecting on his own pattern of injury -

“When you’re feeling good, rather than increasing load by 10%, you should probably decrease load by 10%”.

Feeling good means you may well be at the peak of a training cycle and rather than pushing on even harder, an easy week absorbing your training and enjoying the benefits of improved fitness may be what you really need.

As small wins accumulate, you gradually gain more confidence in your body.

Every run is a battle between current capacity vs load

We’ve zoomed out and looked at weekly/monthly training practices that can be optimised, leading to safely building your physical capacity and protect you against injury.

But that is only half of the equation…

The second half of the blog will focus on zooming in and seeing what happens every time you perform a training run or competition at the micro-level.

As a rehab community, we’ve had a big focus on the load and talking about training practices, but not as much focus on the readiness, or capacity of our bodies to match that load.

Essentially every training session is a battle between your current capacity (which can fluctuate daily) and the load you’re applying.

In an ideal world you would structure your training so there are only incremental differences in the demands of training and your current capacity.

A process that stimulates continual positive adaptations in your fitness (see graph below).

Key point: your physical capacity can vary significantly day by day

We can apply the same load on two different days - and have two significantly different results.

There are a number of important modifying factors that decrease your physical capacity in the short-term.

These factors may include things such as:

Inadequate fueling (dehydration or lack of carbohydrates / glucose)

Digestive issues

Injury

Soft tissue issues e.g. excessive tightness or neuro-muscular inefficiencies

Inadequate recovery from previous session

Static stretching right before a run

Poor sleep

Decreased motivation

High stress levels

Long work hours

Excess sitting

Other lifestyle factors e.g. excessive alcohol consumption

Inappropriate equipment e.g. worn shoes

Caffeine (lack of)

Viral illness

Altitude

Non-modifiable factors:

weather e.g. high humidity, wind e.t.c

age

gender

pregnancy

serious illness / accidents

The more of these modifiable factors you have in a given training session or competition - the bigger the gap or mismatch between your capacity and demand, thus the greater risk for developing an injury.

Key point:

Significant spikes in training load can be a result of a mis-match in current capacity vs training load (e.g. too much training, or a body that has dropped in capacity).

These modifiable factors may be present on a particular day, or they might lurk in the background over months/years.

For example being nutritionally deficient in calcium or vitamin D can pre-dispose you to stress fractures, which develop over months.

Becoming aware of these modifiable factors (and there are plenty more that haven’t been listed) is huge step to avoiding over-training and injury.

Ultimately it means you can set realistic expectations and work towards them.

Getting the most out of your training sessions

Managing your modifiable factors can be a way to manipulate your training to make it easier or more challenging.

As you gain more experience, you can start to play around with the variables to cause positive stress to your system.

Obviously on race day, you’re looking for your physical capacity to be 100% to give your best performance.

Sometimes it doesn’t always work out like you had hoped.

An example: My Melbourne Half-Marathon disaster.

The best example I can give you came last year at the Melbourne Half Marathon in October.

I was going for a PB in the half-marathon and thought I had done enough in my training build-up to warrant giving it a good crack.

But I was to be brought down to earth quite dramatically!

These are some of the factors that lead me to a dramatically lower capacity on the day of the half-marathon:

we did a road trip from Adelaide over 2 days, arriving the evening before the half marathon and then spent another 1 hour in the car driving to the race the following morning - so my hip flexors were incredibly tight

had a 2 month old son who was awake during the night, which meant very little sleep

nutrition in the lead up to the race was very average - being on the road and eating a lot of crap

alcohol consumption - we were staying with my father in law - so just to be social a few beers were consumed the night before the run

de-hydrated - it was an unusually hot and windy day in Melbourne

late to the start line - so a little stressed and missed out on running with my pace group, so battling to catch them in the first 5km and running way above my goal pace

This culminating in getting to the 10k mark completely spent - and I was forced to walk and shuffle to the finish line completely burn out and no where close to a PB.

You’re a different runner every time you run

Running coach Greg McMillan states you’re “a different runner every time you run” and you need to appreciate the subtleties of your what you’re feeling every day (he talks about this in depth on Tina Muir’s Running for Real Podcast).

When you’re not feeling great, forcing bad workouts rob you of confidence and increase your chance of injury.

Taking charge of your own training by modifying and adapting your training means you can string some solid weeks of training together - putting you on the fast track to performance and becoming un-breakable.

Many elite athletes follow these principles - for example Kara Groucher stated that if only two out of every three scheduled training sessions go ahead as planned, that is a really good result.

She and her coach are happy to improvise if she isn’t feeling great or still recovering from her previous workout, possibly scrapping the session altogether.

So never be afraid to modify and adapt your training until you a state of readiness.

This internal awareness / intuition and being open to adapting your training on a daily basis is where the game can be won and lost.

It involves a process of constant decision making and listening to your body.

All scheduled workouts should be considered provisional, until you get a feel of what your capacity is on the day.

Brad Hudson and Matt Fitzgerald summed it up perfectly in their book, Run Faster - From the 5k to the Marathon:

“The art of coaching, or self-coaching, is fundamentally a matter of taking a systematic approach to training that makes better performance more or less inevitable, if not entirely predictable.

It begins with the premise that you cannot predict the future - or specifically how your body will respond to training.

Therefore every workout is treated as an experiment.

You then allow the results of these experiments to guide you toward a future of running faster.

Training patterns that seem to hold you back are eliminated, while those that seem to push you forward are kept and possibly increased or intensified.

Sooner or later this approach is bound to lead you to new personal best performances”.

How to adapt your training

If you’re aren’t feeling great, you don’t have to fully take a day off training. Here are some other options:

have an easy restorative run instead of doing a session

cross train with a swim, walk or hike in nature instead of run

double down on nutrition, massage, sleep

yoga class - especially restorative

pilates class to get your deep core stabilisers switching on

But having a good pain threshold and learning to push through is a good thing, right?

Well, as always - it depends.

Sometimes having the ability to dig deep in spite of less than ideal conditions can be very helpful.

In fact training to be ‘anti-fragile’ means getting out there and chasing challenging situations that make your stronger and more resilient.

Intelligently and judiciously using these modifiable factors in training can make training tougher to (hopefully) make race day easier.

Hard training and suffering is important - but being smart about how often and when you push yourself into the red zone is the key.

Conclusion

I know it’s been a long read - so great job for getting this far…I hope it’s been useful for you.

A big thanks to legends Tim Gabbett and Michael Nitschke who inspired this blog.

Please share with your friends who you think might find it helpful.

Stay tuned for next months final chapter, Recovery.