“I can’t understand why I’m getting injured so often.

I always stretch before I exercise.

I’m confused!”

A phrase I hear in the clinic on a daily basis.

Just to clarify, in terms of ‘stretching’ we are talking about holding a static muscle stretch.

Optimising mobility, (especially around a joint) is another thing altogether and can be a very useful way to prepare the body for the demands of sport.

Knowing where and when to perform joint mobility exercises and foam rolling can be invaluable - but we’ll talk about that another time.

5 Times When Stretching Is Not A Good Idea

Right before a training session/race

There is a growing scientific argument that pre-exercise muscle stretching is generally unnecessary and may even be counterproductive, increasing the risk of injury and decreasing performance.

Researchers have shown that static stretching reduces strength by about 5 percent.

Certainly not an ideal way to start a race, where you will be placing big demands on your muscular system, and creating risk of overload and injury with a weaker muscles.

In terms of performance, a study of runners completing a 1 mile run - those who stretched before hand were slower at running the mile by a full thirteen seconds.

And this study found that runners had who stretched before had a higher rating of perceived exertion during their run.

Stretching aims to loosens muscles and their accompanying tendons.

But in the process, it makes them less able to store energy and spring into action, essentially creating a temporary reduction in available capacity.

Instead of static stretching, focus on a proper warm-up involving running at an easy pace for 10-15 mins (aim to break a sweat) and gradually layering in sport specific drills.

You can tune your body by activating the specific stabiliser muscles that may be required in your sport and create joint mobility where you need it.

Dedicating some time to stretching and mobility work (Yoga, Pilates e.t.c) during the week is a very good idea, just not right before you exercise.

If you need some help with your warm-up routine, just let us know.

2. When you have a painful and irritated tendon

For example if you have hip pain, (often when the hamstring and gluteal tendon have become irritated) - many people intuitively try and ‘stretch it out’ to get some relief.

Stretching can sometimes make you feel better temporarily.

But it’s not until later (often that night) that the pain is becomes a problem.

Aggressively stretching tendons irritates them by compressing them and this can delay the healing process.

The most important thing for tendons is to gradually increase their capacity and tolerance to load, via a graduated strengthening program under the supervision of a Physiotherapist.

3. Chronic lower back pain

Research shows people who focus exclusively on stretching their lower backs actually had a greater risk for developing back pain.

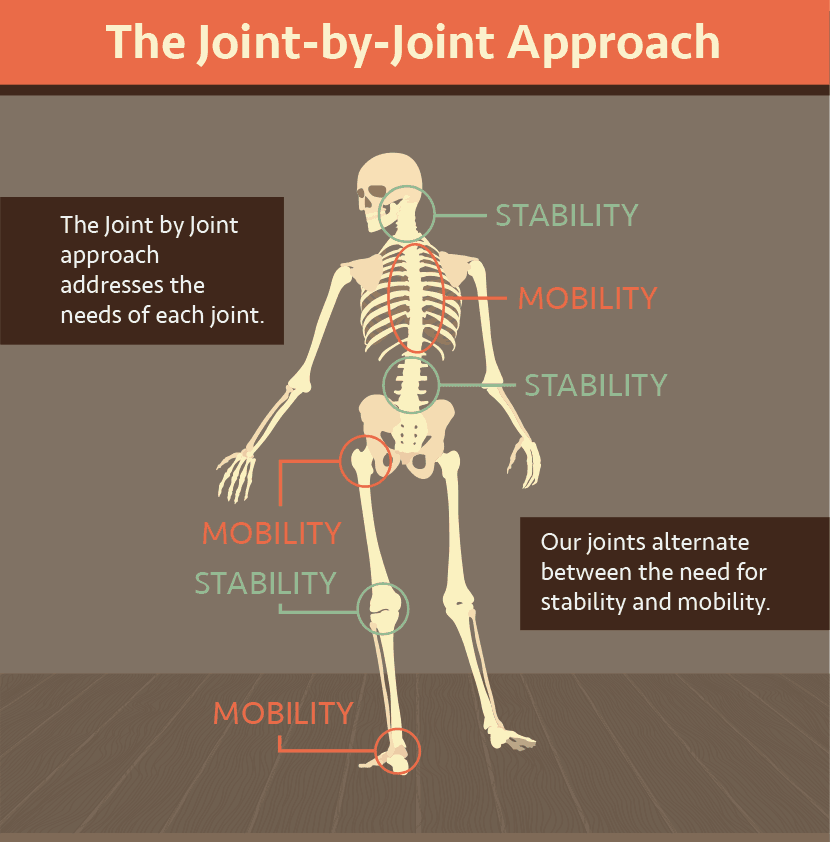

This comes back to a bigger picture view of the body and the role of each segment (see The Joint-by-Joint picture below).

We can see the main role of the the lower back is to provide stability - the core from which the rest of the body can move freely.

Stretching the lower back may feel good temporarily, and there is absolutely no issues with adding stretching to your overall program, especially if it makes you feel good.

But stretching doesn’t build capacity and if you have ongoing back pain, you will need to develop a program of building core strength and capacity to help in the long run.

Getting the balance right between mobility and stability is the trick for lower back pain.

To get you started, check out a 6 Minutes To A Supple Spine routine that you might find useful and you may want to try a KIN Foundation Class.

4. To try and improve your hamstring flexibility

The primary role of the hamstrings in walking and running is to eccentrically control the landing of the foot.

Eccentric refers to a type of contraction where a muscle lengthens while contracting.

Whilst it is important to have adequate flexibility, the actual more important job of the hamstring to have enough strength and capacity to walk and run properly.

If a muscle doesn't have much capacity to contract when needed, it will most likely get overloaded.

When it gets overloaded, it's muscle fibers contract and knot up, limiting flexibility.

For a runner, strength and stability trumps flexibility everyday of the week.

Hang on a sec...I thought stretching was a good thing!?

Stretching the hamstring in this position, you are actually making the hamstring weaker and sending confusing mixed messages to the brain about what the function of the muscle is.

Anytime your brain is confused, it's going straight into fight-flight mode and will want to tighten everything up to protect it.

Intuitively stretching feels good and it often does give some short term relief.

But in the long run, with continued stretching, the hamstring becomes weaker and more likely to become overloaded and tight. Then you've got yourself into a real pickle.

The hamstring, once locked down, becomes an inefficient blob that hampers everything you try and do.

Our first step in making friends with the hamstring is to stop making it angry, so no more stretching.

For more info on how to become friends with your hamstring - please click here.

5. Your sore neck

If you have neck pain, a first line of treatment that many people try is stretching.

But being over-zealous with your neck stretches could potentially do more harm than good.

With too much stretching, we can run the risk of irritating the vertebrae, compressing the discs and pinching nerves.

A general rule of thumb is that your neck stretches should be gentle, never feel painful and avoid pushing to the extreme ends of motion.

If you have any uncertainty in regards to cervical stretches you are currently performing, schedule an appointment to ensure that your neck does not become a pain in the neck.

In the long term, performing exercises to improve your neck and shoulder strength can be more useful than only stretching.

Maintaining good cardio-vascular fitness is extremely important, as well practicing appropriate stress reduction techniques and having a good ergonomic set-up (and not always looking down at your phone!).

Have you any questions about stretching?

Please leave any comments below…

And if you have any ongoing niggles, please schedule an appointment to come in and see us.

We can get to the root cause of your problem and get you back on the fast track to doing what you love.