If you’ve ever been told “your knee is worn out”, “your scans explain everything”, or “you’ll just have to manage it”, I want to offer you a different way of understanding pain — one that actually makes sense of real life.

This idea comes from two very different people:

An orthopaedic surgeon who spent his career operating on joints

A neuroscientist who studied how the brain senses the state of the body

They worked in different worlds, but they arrived at the same conclusion.

The Joint Has a “Comfort Zone”

Orthopaedic surgeon Scott Dye described something called the Envelope of Function.

You don’t need the fancy name.

It simply means this:

Every joint has a range where it feels calm, safe, and comfortable.

Inside that range:

You can move

Load feels fine

Pain stays quiet

Outside that range:

The joint becomes sensitive

Pain shows up

Things feel “angry” or reactive

Here’s the important part:

Pain doesn’t mean damage.

Pain means you’ve exceeded your current capacity.

That capacity can change — up or down — depending on what’s going on in your body and life.

Pain Is the Body Asking for Help, Not Sounding an Alarm

Neuroscientist Bud Craig took this idea even further.

He showed that pain isn’t just about tissues.

Pain is part of the body’s internal monitoring system — the same system that tracks:

Fatigue

Inflammation

Energy levels

Stress

Recovery

In simple terms:

Pain is how your body lets you know that its balance is under strain.

Not broken.

Not damaged beyond repair.

Just out of balance.

Why Scans Often Don’t Explain Pain

This explains something many people experience:

Two people have the same scan

One has pain, the other doesn’t

Why?

Because scans show structure, not capacity.

They don’t show:

How well tissues are fueled

How rested the system is

How much load you’ve been carrying

How stressed or inflamed your body feels

Pain lives in the relationship between load and capacity — not in a single image.

The Big Shift: From “Fixing” to “Rebuilding”

Once you see pain this way, the goal changes.

Instead of:

“How do I fix this part?”

“What’s wrong with my knee?”

The better questions become:

“What is my system able to handle right now?”

“How do I gently expand that capacity again?”

This is why:

Pushing harder often backfires

Rest alone rarely solves the problem

Quick fixes don’t last

What works is gradual, intelligent rebuilding.

Why This Is Actually Good News

This perspective is hopeful — not dismissive.

It means:

Your pain is real

Your body isn’t broken

And improvement is possible

Capacity can grow.

Tolerance can return.

Confidence can come back.

Not by forcing.

Not by fearing.

But by working with the body instead of fighting it.

One Line to Remember

If you remember nothing else, remember this:

Pain appears when load exceeds current capacity — and fades as capacity is rebuilt.

That’s it.

That’s the whole model.

And it’s the lens I use every day when helping people move forward — calmly, steadily, and with far less fear.

What the Research on Load and Injury Actually Shows

This idea isn’t just theoretical.

Sports scientist Tim Gabbett has spent years studying why people break down — from elite athletes to everyday movers.

His key finding is surprisingly simple:

Injury and pain are most likely when load increases faster than the body’s capacity to adapt.

Not because the body is weak.

Not because joints “wear out.”

But because the dose of stress exceeded what the system could currently handle.

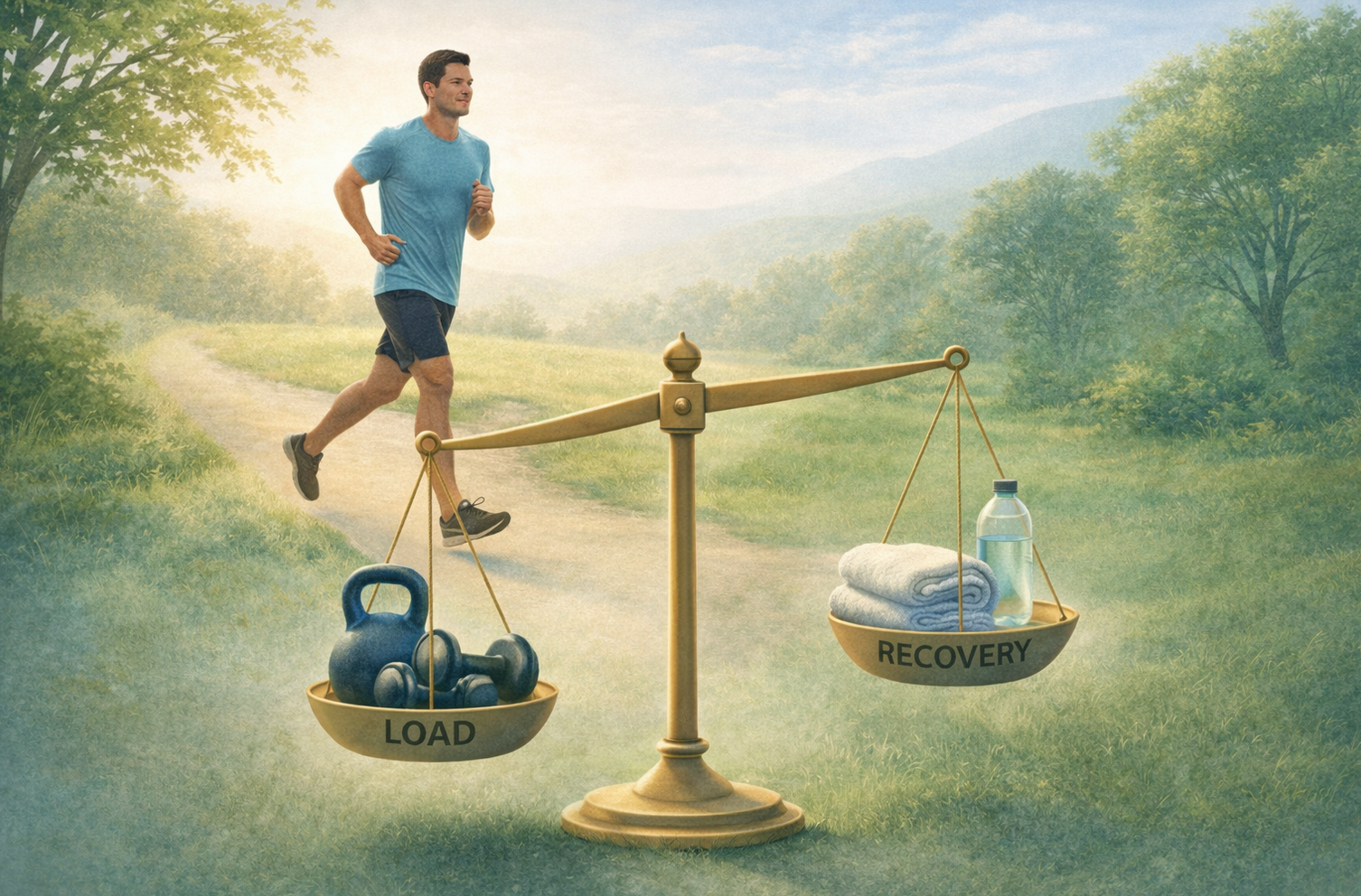

Growth Follows a Simple Formula

When you strip away the noise, recovery and resilience come down to this:

Appropriate stress + appropriate recovery = growth

That’s how:

Muscles strengthen

Tendons adapt

Joints become more tolerant

Confidence returns

Too much stress without recovery → symptoms

Too little stress → loss of capacity

Pain often sits right in the middle — when the balance has been lost.

This Is Why “Wear and Tear” Misses the Point

If pain were just about wear and tear:

Athletes would be in pain all the time

Older bodies couldn’t adapt

Rest would fix everything

But that’s not what we see.

What we see is that capacity is trainable at any age — when load is dosed well and recovery is respected.

That’s a very different story from protection, avoidance, and fear.

The Real Goal

The goal isn’t to protect your body from stress.

The goal is to rebuild your ability to handle it.

Not by forcing.

Not by pushing through pain.

But by applying the right amount of challenge — and giving the system time to respond.

That’s how resilience is built.

That’s how pain settles.

That’s how people return to living fully again.